Landscape photography is about more than capturing beautiful scenery—it's about creating visual narratives that evoke emotion and connect viewers to the natural world. While technical aspects like exposure and focus are important, composition is the artistic foundation that transforms ordinary scenes into extraordinary photographs.

The Art and Science of Landscape Composition

Composition in landscape photography refers to how you arrange elements within your frame. Effective composition guides the viewer's eye through the image, creates a sense of depth and dimension, and communicates your creative intent. Let's explore powerful composition techniques that will elevate your landscape photography.

1. The Rule of Thirds: Beyond the Basics

The rule of thirds is often the first composition technique photographers learn—divide your frame into a 3×3 grid and place key elements along these lines or at their intersections. But there's more to this principle than simply following a formula.

Advanced applications:

- Place the horizon on the upper third line to emphasize the foreground, or on the lower third to highlight dramatic skies

- Position key elements (like a mountain peak or solitary tree) at intersection points for maximum impact

- Use the rule as a starting point, then make intentional decisions to break it when the scene demands a different approach

Try this: Photograph the same landscape with the horizon at different positions (lower third, middle, upper third) and compare the emotional impact of each composition.

2. Leading Lines: Creating Visual Pathways

Leading lines are powerful composition tools that draw the viewer's eye through your image toward your main subject or into the distance. They create a sense of depth and dimension in the two-dimensional medium of photography.

Types of leading lines in landscapes:

- Explicit lines: Roads, paths, rivers, fences, shorelines

- Implicit lines: Patterns of light and shadow, tree alignments, mountain ridges

- Converging lines: Elements that create perspective by appearing to meet in the distance

- Curved lines: S-curves and winding paths that create a more gentle, meandering flow through the image

Technique tip: When using leading lines, ensure they lead somewhere meaningful. A path that leads the eye to nothing of interest wastes the power of this composition tool.

3. Foreground Interest: Creating Depth

One of the biggest challenges in landscape photography is translating the three-dimensional world into a compelling two-dimensional image. Strong foreground elements help create a sense of depth and invite viewers to step into your photograph.

Effective foreground elements:

- Interesting rock formations or boulders

- Patterns in sand, ice, or snow

- Wildflowers or distinctive vegetation

- Reflections in still water

- Textures like moss, lichen, or weathered wood

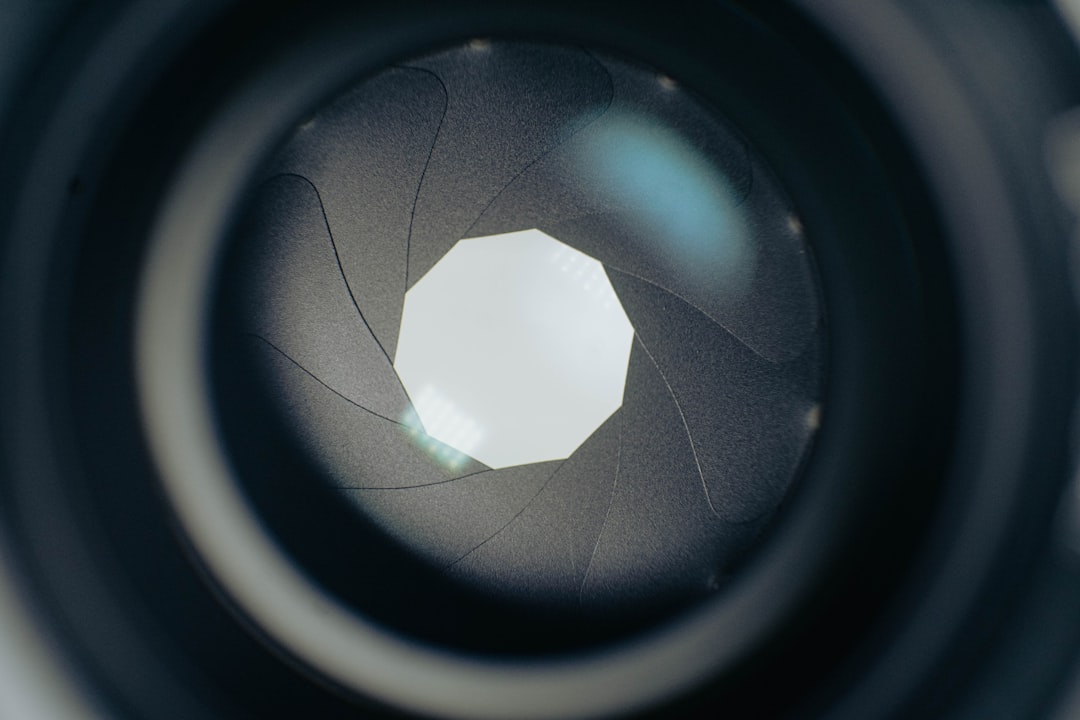

Composition tip: Use a wide-angle lens (16-35mm range) and get close to your foreground element—often within a few feet or even inches—while maintaining focus throughout the scene with a small aperture (f/11-f/16).

4. Framing: Natural Borders

Natural frames within your landscape create structure, add depth, and focus attention on your main subject. They create a "picture within a picture" effect that can be extremely powerful.

Natural framing elements:

- Archways in rock formations

- Overhanging branches or tree trunks

- Cave or cliff openings

- Mountain passes or valleys

- Architectural elements in environmental landscapes

Creative approach: Experiment with partial frames—you don't need to surround your subject completely. Even framing just two sides can create a strong composition.

5. Layering: Visual Progression

Layering creates a sense of depth by organizing the landscape into distinct planes from foreground to background. This technique is particularly effective in misty conditions or when photographing multiple mountain ridges.

Creating effective layers:

- Look for natural separations in the landscape (valleys between hills, fog between mountain ranges)

- Use contrasting tones or colors between layers to create separation

- Arrange elements so they don't overlap confusingly

- Use a telephoto lens (70-200mm) to compress layers and emphasize the separation

Advanced technique: Use graduated neutral density filters or exposure blending to control the light balance between different layers, preventing bright skies from washing out while maintaining detail in darker foreground elements.

6. Balancing Elements: Visual Harmony

Balance in composition refers to the distribution of visual weight throughout your frame. A balanced image feels stable and complete, though balance doesn't necessarily mean symmetry.

Types of balance:

- Formal/Symmetrical balance: Similar elements on either side of the frame, often effective with reflections

- Informal/Asymmetrical balance: Different elements that counterbalance each other (a large boulder on one side balanced by a cluster of smaller rocks or a colorful element on the other)

- Radial balance: Elements arranged in a circular pattern around a central point

Visual weight factors: Size, color intensity, contrast, isolation, and complexity all contribute to an element's visual weight in the frame.

7. Scale: Conveying Size and Grandeur

One of the greatest challenges in landscape photography is conveying the true scale and majesty of grand scenes. Without reference points, viewers can't appreciate how massive that mountain or waterfall truly is.

Including scale references:

- People in the landscape (even tiny in the frame)

- Recognizable objects like trees, buildings, or vehicles

- Wildlife appropriate to the setting

Ethical consideration: When including people for scale, be mindful of overcrowded natural locations. Never stage photographs that could encourage others to venture into fragile ecosystems or dangerous areas.

8. Negative Space: The Power of Simplicity

Negative space—the empty areas around your main subject—can be as powerful as the subject itself. Minimalist landscape compositions use negative space to create striking, contemplative images.

Effective use of negative space:

- Clear, open skies around a solitary mountain or tree

- Expanses of calm water with minimal elements breaking the surface

- Snow fields with isolated features

- Fog that obscures all but the essential elements

Composition tip: When using negative space, the quality of that space matters—look for gradient tones, subtle textures, or delicate color variations to add interest to seemingly "empty" areas.

9. The Golden Ratio and Spiral: Mathematical Harmony

The golden ratio (approximately 1:1.618) is a mathematical proportion found throughout nature that humans find inherently pleasing. The Fibonacci spiral, based on this ratio, can create compositions with natural flow and harmony.

Applying the golden ratio:

- Use the golden spiral as a template for arranging elements (many cameras and editing software offer this as a composition overlay)

- Place key elements at points where the spiral changes direction

- Allow the viewer's eye to follow the natural spiral movement through your image

Pro tip: Don't get too caught up in mathematical precision—the golden ratio is a guide, not a rigid rule. Trust your intuitive sense of balance and flow.

10. Breaking the Rules: Intentional Composition

The most powerful compositions often come from knowing when to break conventional rules. Once you understand composition principles, you can make deliberate choices to create tension, drama, or unconventional beauty.

When to break composition rules:

- Centering the horizon for perfect reflections or symmetrical scenes

- Deliberately creating unbalanced, tension-filled compositions for dramatic effect

- Using extremely minimal or maximal approaches that ignore traditional composition guidelines

- Creating abstractions that focus on color, texture, and form rather than recognizable landscape elements

The key difference: Breaking rules with intention and purpose versus breaking them through lack of awareness.

Practical Exercise: Composition in the Field

Next time you're photographing landscapes, try this exercise to develop your compositional eye:

- When you find a scene you want to photograph, take your first, instinctive composition

- Then force yourself to create at least five different compositions of the same scene by:

- Changing your position (higher, lower, left, right)

- Switching between horizontal and vertical orientations

- Using different focal lengths

- Applying different composition techniques from this article

- Review your images later and analyze which compositions worked best and why

Conclusion: Developing Your Compositional Voice

Great landscape composition is both technical and intuitive. While these principles provide a foundation, your personal style will emerge as you practice and develop your unique way of seeing the world.

Remember that composition isn't about following rigid rules but about making intentional choices that serve your creative vision. The most compelling landscape photographs don't just show what a place looks like—they communicate how it feels to be there.

In future articles, we'll explore how light, weather conditions, and seasonal changes influence landscape photography, and how to combine these elements with strong composition for truly exceptional images. Stay tuned!